This website is not being maintained. An archived version of this blog article is here

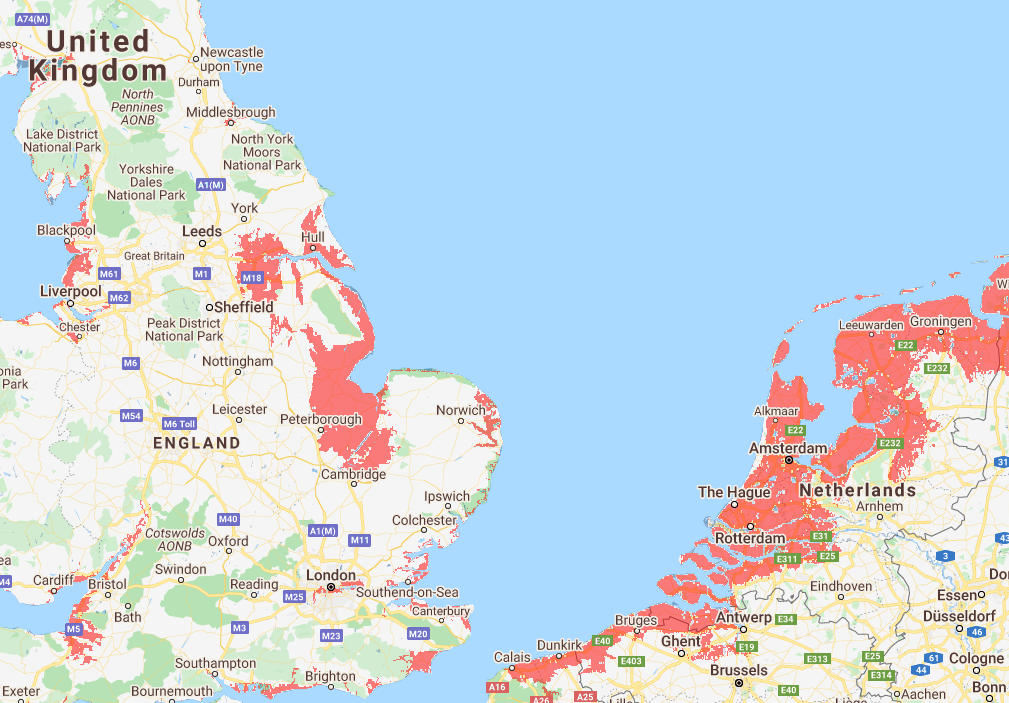

There was a shocking map published recently, based on new scientific research, of "Land projected to be below annual flood level in 2050". "Improved elevation data indicate far greater global threats from sea level rise and coastal flooding than previously thought." And if you look at the map, one country jumps out immediately.

(Image credit: Climate Central, Inc)

Wow. From looking at this map you might think that approximately HALF of The Netherlands will be underwater in a mere 30 years. Goodbye to The Hague and Rotterdam, and Amsterdam forecast to become an island in the North Sea.

Is this for real? Well... partly yes and partly no. Firstly, you need to know one important fact about this forecast, which the authors mention in the research paper:

"Globally at present, levees and seawalls protect low-lying populations in many major deltas, such as around Shanghai, the Netherlands and New Orleans [...]. However, levee location data are not globally available, to our knowledge, and so are not incorporated into this analysis."

In other words, the Netherlands' famous sea defences, which even now keep the people dry and the land arable, are treated in this map as if they didn't exist. The map might be useful for many places - especially highly vulnerable places like Bangladesh - but we should probably not take this picture of the Netherlands too literally.

With a large part of the country lying below sea level, The Netherlands have a long history of battling against the water. After the disastrous North Sea flood of 1953, which killed around 2000 people and huge numbers of livestock, while damaging 200,000 hectares of land, the Delta Works were developed. This complex set of infrastructure projects including dykes, dams and storm-surge barriers, was implemented to protect the country from future floods.

There's a similar story for London too. In London there is the Thames Barrier, a massive flood barrier which protects London against storm tides and so on. The UK and Netherlands have a common history here: the UK was hit by the same flood in 1953, with about 300 UK residents killed. The Thames Barrier was the London equivalent of the Delta Works in response to this disaster.

The Thames Barrier was intended to protect London against a "once every 100 years" level of flooding, while the Delta works were in many cases designed against "once in every few thousand years" flooding - clearly more ambitious. Still, the Thames Barrier protects London against the watery 2050 shown on that map.

However, both the Thames Barrier and the Delta Works are not going to protect us forever. Sea levels are now rising at a fast rate due to thermal expansion of seawater and melting ice sheets and glaciers. Both countries are going to have to spend huge amounts of money to defend themselves against the impact of sea level rises. The Thames Barrier for London is likely to be superceded by a second much larger barrier downstream, which might even have energy-generating turbines built in. (This is part of the "Thames Estuary 2100" plan.)

(What about other places in the UK? The Fenlands (near Cambridge), and the area around the Humber (Hull, Yorkshire), both look to be at risk. They're large coastlines, quite hard to protect with a simple Thames-like barrier. What does the UK plan to do there? We don't know - we've heard almost no discussion of this. If you do know, let us know!)

So what about the Netherlands? If the flood map at the start of this article is too pessimistic, then what is the more likely scenario? In a fantastic (and terrifying) longread in the magazine "Vrij Nederland", several experts gave their predictions and discussed the strategies available for dealing with extreme sea level rises. The most extreme prediction for the year 2300, based on a temperature increase of 3 to 4 degrees, was sketched out, and the result is quite a lot like the map given above. In this scenario, sea levels have risen by 3 meters in 2100, and by 15 meters in 2300.

Yes, the given scenario is extreme, but not impossible. There is a lot of uncertainty about how much the sea levels will rise. Two main factors of uncertainty at this point: the degree to which the world will manage to curb its carbon emissions, and the rate at which the Antarctic ice sheet will melt. This uncertainty is exactly why a public debate (and more research funding) is necessary.

One thing to bear in mind is that the rising sea of levels is a slow process. So slow, that even if we stopped all CO2 emissions today, sea levels would continue rising, because of the greenhouse gas emissions that already happened in recent years. To put that into numbers: even if all countries meet their commitments of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, emissions between now and 2030 will still contribute to a sea level rise of about 20cm by 2300 - about the same amount levels have already risen since 1900.

That is the most positive scenario, one in which all countries have reached their reduction targets by 2030, and produce absolutely ZERO emissions from 2030 onwards. And remember those 20cm would be in addition to the sea level rise due to past CO2 emissions which has yet to take its full effect. A recent IPCC Special Report states that sea level rise, compared to the reference period between 1986-2005, “could reach around 30-60 cm by 2100 even if greenhouse gas emissions are sharply reduced and global warming is limited to well below 2°C, but around 60-110 cm if greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase strongly.”

The current Delta Works offer protection for an increase of up to 40 cm. The future Dutch adaptation plan, the ‘Delta Programme’, is based on slightly older IPCC sea level projections of a maximum of 98 cm sea level rise by 2100. A revised programme is expected by 2027.

The Dutch Royal Meteorological institute (KNMI) has also made its own projections specifically for the Netherlands, as sea level change will not be the same globally. With a temperature increase of about 2°C, sea level rise along the Dutch coast could be up to 2 meters by 2100. With a temperature increase of about 4°C, it could be up to 3 meters (this is the most extreme scenario from the 'Vrij Nederland' article).

Here are all the numbers in one plot (most extreme KNMI scenario not plotted):

Sea level rise projections by the IPCC (global) and the KNMI (Dutch coast). The IPCC uses a 66% confidence level, i.e. there is a 66% chance of the actual value being within the range shown, 17% chance that it will be lower, and 17% chance that it will be higher. The KNMI projection uses a 90% confidence level, so there is only 5% chance of the level being lower and 5% chance of the level being higher than the range shown in the graph.

‘RCP 2.6’ is the IPCC’s most positive scenario, in which we keep well below a 2°C temperature increase. ‘RCP 8.5’ is the worst-case scenario with a temperature increase of 4°C. RCP 4.5 is one of the two intermediate scenarios. It is unclear whether KNMI’s RCP 4.5 truly aligns with the IPPC’s RCP 4.5.

Looking ahead to future centuries, what should the Netherlands plan? One of the suggested strategies that the "Vrij Nederland" article discussed is to retreat - to Germany, allowing the sea to reclaim part of the Dutch low lands. Simply accepting that the northern and westerns parts of the country would be gone. This is a really big deal, and discussed surprisingly little in politics and the media.

We have been working on this article for a while. In the mean time, on January 29th, Dutch historian and journalist Rutger Bregman published a mini-book entitled 'The Water is Coming' ('Het water komt'). It was distributed for free, discussed in a popular talk show, and a short version published in one of the most read national newspapers. Perhaps this will finally be the trigger for the conversation to move into the mainstream?

Read and see more

Longread (Vrij Nederland), February 2019:

Dutch: "De zeespiegelstijging is een groter probleem dan we denken. En Nederland heeft geen plan B"

English: "In face of rising sea levels the Netherlands ‘must consider controlled withdrawal”

If you'd rather watch than read, there is this documentary on rising sea levels in the Netherlands (in Dutch), Tegenlicht, September 2019: https://www.vpro.nl/programmas/tegenlicht/kijk/afleveringen/2019-2020/waterlanders.html

Mini-book, in Dutch:"Het water komt", January 2020, by Rutger Bregman

Government documents on sea level rise:

UK: "Exploratory sea level projections for the UK to 2300", full report and summary

NL: "Zeespiegelstijging nu en in de toekomst"

(Top image: Oosterscheldekering, part of the Dutch Delta Works. Credit: Rijkswaterstaat)