This website is not being maintained. An archived version of this blog article is here

Europe's rate of installing solar power capacity has more than doubled in the past year. The leading countries in that surge to install over 16 gigawatts of new solar are Spain, Germany, and - coming third, a massive achievement given the other countries are so much larger - the Netherlands.

But wait a minute. What about the UK? The 2014 "PV Barometer" report announced that the UK was the "major European Union solar market of the future". "The country has committed to maintaining its aid mechanisms through to 2020 [...] The Minister of State for Energy says that the UK could install up to 20 GWp of solar capacity by 2020." So, is the UK near the top now?

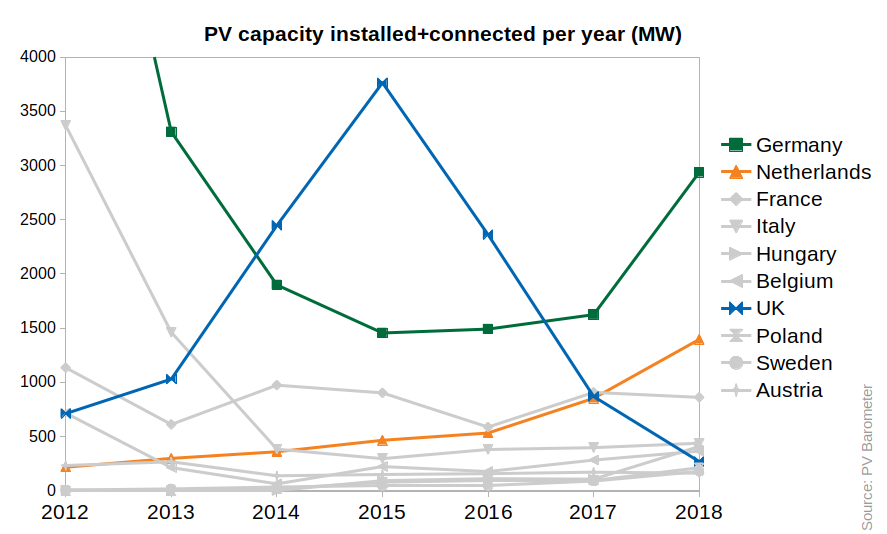

Well... this graph shows some of the drama. The amount of solar capacity installed - per year, per country.

The UK really was riding high in 2014-2015 - but then it nose-dived. In the most recent annual figures (2018) the UK installed-and-connected 271 megawatts, which is less than one-tenth of what it was, and less than one-fifth of what the Netherlands installed in the same year.

So what happened?

One rather blunt answer is: the Conservative Party. In the election of May 2015 the Conservatives won a majority in the UK Parliament (after having been in coalition government). In July 2015, the government's budget made some uncomfortable changes for the renewable energy industries - such as suddenly taxing renewable energy under the "Climate Change Levy", a scheme intended to tax CO2-emitting energy sources (!). Then on the 27th of August 2015, the UK government released a consultation document heralding some further intentions. And their intentions were much harsher than industry commentators had expected.

The 2015 proposal was to cut rooftop solar's feed-in-tariff (i.e. the guaranteed payment people would get for generating electricity for the grid) by more than two-thirds. It's quite common for regulatory changes to phased in, and that helps businesses adapt, but this dramatic change was brought in all at once. Amber Rudd (the minister in charge) claimed the change was to prevent cost overruns.

This had immediate and sad consequences. Projects such as "Repower Balcombe", a community energy scheme in a UK village that had been in the news, had to cancel their plans. And as you saw in the graph above, the UK's solar power boom, riding high in 2015, suddenly crashed. Four UK solar power firms went into liquidation within two weeks.

And how about that forecast from 2014, of 20 gigawatts of power by 2020? It's currently standing at around 13, and will not be reaching 20 any time soon.

The Netherlands is doing remarkably well at the moment. They may have been slower to get going - as the 2018 "PV Barometer" described it, "Laggards such as France and the Netherlands have been spurred into action now that costs have been slashed." As of 2018, the installed capacity per inhabitant in the Netherlands is 250 Watts, outshining the UK's 197 Watts per person. There's still room to go further, to catch up with our strongest nearby neighbours: Belgium has 373, and Germany a phenomenal 547 Watts per person in the country.

But - regulation-wise - it's not all straightforward in the Netherlands either. Back in 2008 a subsidy scheme was introduced, but this was curtailed within a few years after relatively low uptake. To replace it, in 2013 solar panels were made tax-deductible, and for domestic solar a "net metering" (salderingsregeling) scheme has been in place for almost a decade.

"Net metering" means that if your solar panels generate 1 kilowatt-hour in the daytime, and then you use 1 kilowatt-hour in the evening, those kilowatt-hours can cancel each other out when it comes to billing. There are some drawbacks of net metering - for example, it assumes that the value of a unit of energy is always the same, even though demand can vary massively. It can can be quite simple to implement, as long as you have an electricity meter that can count downwards as well as upwards (!). However, I think it's fair to say that "feed-in tariff" schemes are generally considered better than net metering. A feed-in-tariff scheme typically offers a long-term contract with a specified price-per-kWh paid.

The UK brought in its feed-in-tariff ("FiT") in 2008, the same year as the Netherlands brought in net metering. Perhaps the UK made the better choice that year, because the Netherlands now wants to get rid of net metering. The plan had been that this year (2020) it would start to transition over to a "terugleversubsidie", a FiT-like scheme. However, there were various rumblings about this new Dutch national scheme, until eventually it was delayed until 2023.

The scheme will now begin in 2023, with the old scheme tapering away gradually until 2031. This slow tapering gives ordinary users, as well as businesses, time to adapt to the economics and the practicalities of the new setup. Notice how different this is from the UK Government's much more sudden rule changes in 2015.

There was another wrangle in 2019 about the environment for Dutch solar. A new law came in to restrict the development of ground-mounted solar parks on agricultural land. The law, as it was first proposed, could have halted all solar farm construction for a year, pending further planning debates. However, after debate in the Dutch Parliament the law was toned down. It now acts as a "soft ban" on solar farms in the situation where the equivalent could be achieved through "preferable" projects such as rooftop solar (listed as preferable under the "Zonneladder" preference scheme). In practice this ban is much less dramatic than was feared, because in most projects there's no viable way to get enough rooftops together to substitute for your solar farm plan.

Lessons:

There's one clear lesson here. Regulatory continuity, stability for business, is vitally important. (Oddly, the UK Conservative party often claims it has the better understanding of business than other parties - maybe they should have already understood this lesson?)

It's practically impossible to reverse the impact that the UK's 2015 changes had on the solar industry, e.g. the businesses closed. Yet the solar industry is clearly here to stay, and will be an important part of any country's energy mix, for the foreseeable future. Strategically, any country would love to be a leader in that industry. The regulatory environment is an important part of that.

Read more

- The "Photovoltaic Barometer" reports are good overviews of solar power in Europe, published annually for the past decade.

- "The Netherlands: PV’s Iron Throne" - oddly-titled but a handy summary. (NB it was written before the net metering delay and the soft ban on solar parks.)

- "UK solar power installations plummet after government cuts" (news article from 2016)

(The image at the top of the page: a man in Lekdijk inspects his solar panels. Photo by Tom Jutte)