This website is not being maintained. An archived version of this blog article is here

Among all the debate about carbon capture and new technology to reduce CO2 emissions, one answer is popping up increasingly often: trees.

This beautifully-filmed 3 minute video with Greta Thunberg and George Monbiot gives the big idea:

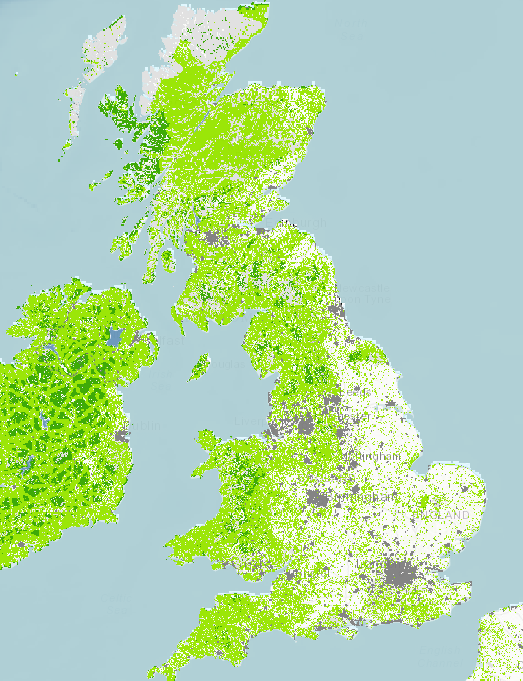

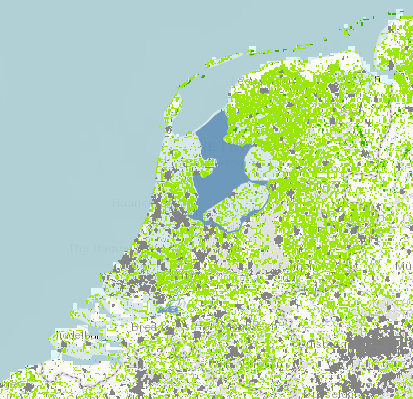

And the numbers stack up too. It's extremely important to protect and restore tropical forest such as the Amazon - but even in the temperate countries of Europe, forests can make a massive contribution: Project Drawdown lists "temperate forest restoration" as their 12th-most important task worldwide, and afforestation (i.e. creating new forests) as the 15th (out of 100 tasks). In the UK alone, afforestation could take 12 megatonnes of CO2e out of the air by 2050 (source, fig 2.8). And this research-based "Atlas of Forest Landscape Restoration Opportunities" shows plenty of land that could be used for restored forest:

In those pictures, dark green areas are areas that could host large-scale forest (e.g. the West Highlands of Scotland), while the more common light green areas are for "mosaic" restoration, with new patchworks of woodland sitting alongside other things.

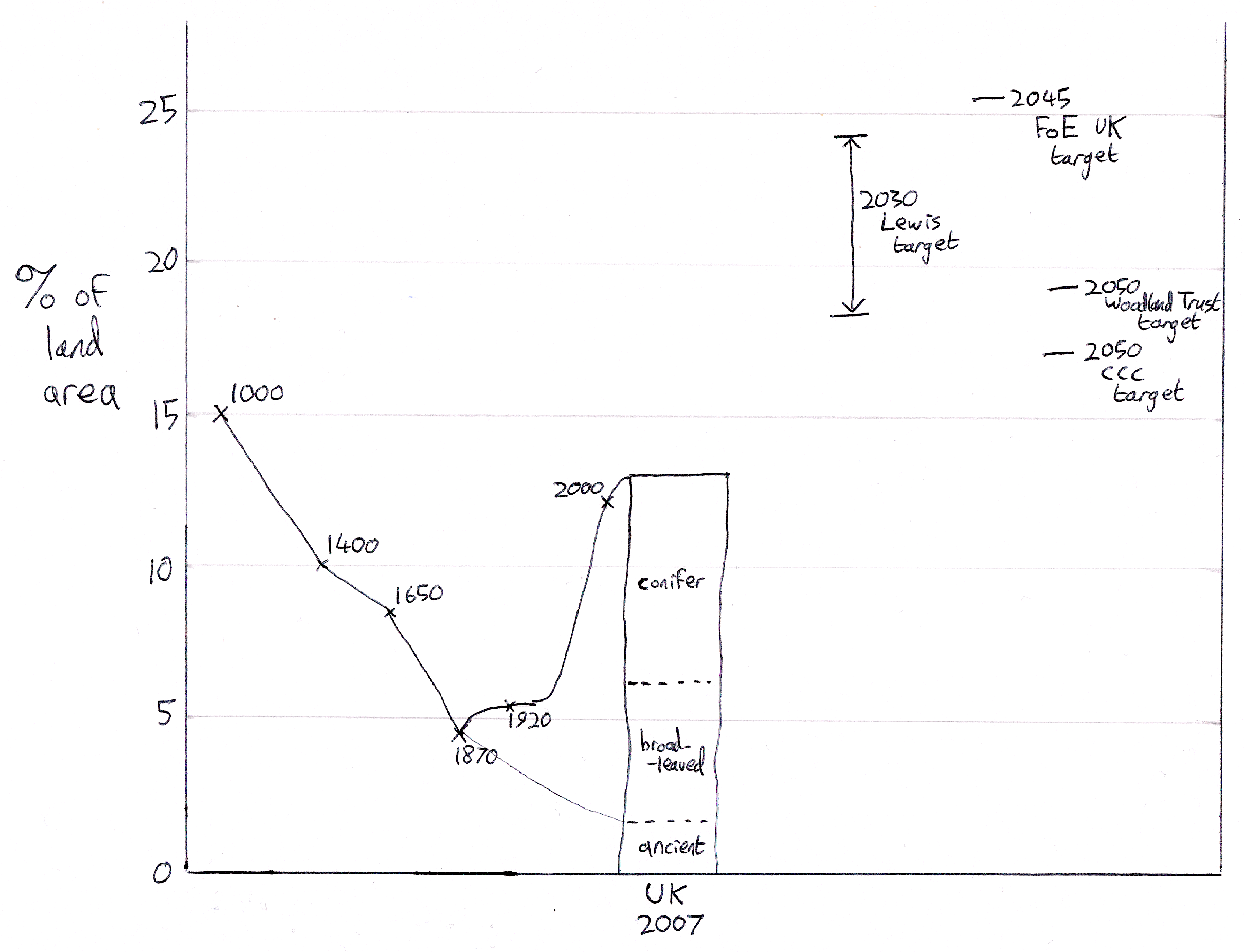

The UK is currently about 13% covered by forest, and the Netherlands about 11%. So how far could we go? How much green should we fill in?

The UK's Committee on Climate Change (CCC) is the official body that advises the government on these things, and they recommend that we need 17% forest cover by the year 2050. But there's quite a healthy competition in the UK for forest-planting goals - everyone's got one! The Friends of the Earth (UK) has a campaign to demand that the UK doubles its tree cover by 2045. They don't actually say how much they mean (double of what number?) but let's take it as doubling from 13% to 26%. That's much more ambitious than the CCC, and five years earlier too.

Simon Lewis (a Professor of Global Change Science at UCL in London) published a great detailed analysis called "Green New Deal for Nature", with targets for the year 2030. He recommended aiming for 18% forest cover, or even up to 24% - similar to the Friends of the Earth, but in just ten years from now. A big task! But he gives good reasons to go for it rather than other strategies: although peatland, for example, can in theory sequester more CO2 per unit area than forest, the UK's peatland is actually an emitter of CO2 not an absorber, because of the way it is managed. It's a good idea to restore degraded peatland - i.e. to fix this - but that can't be done by 2030, it's a longer-term project. Instead, Lewis wants to rewild 25% of the UK (that's a total for woodland as well as peatland) with the mind-blowing goal that it could "sequester 14% of the UK’s annual greenhouse gas emissions each year." For context, that's much more savings than are expected to come from the whole sector of BECCS in the UK. ("BECCS" means "bio-energy with carbon capture and storage" - essentially the industrial/technological approach to removing greenhouse gasses from the air.)

Then, as we were writing this article, a new target appeared! The Woodland Trust published an "Emergency Tree Plan for the UK", aiming for 19% forest by 2050. They give details of how they want to do it: each local council should identify locations and set their own targets, for example, and new housing developments should have one-third of their land covered by trees.

To try and put these into context, let's look at these targets as well as the current and historical tree cover in the UK:

Even as far back as the the year 1000 it seems forest was only 15% of Britain. So are any of these targets possible? Well - Germany has around 30% at the moment, and it's not so different from the UK or NL. And the rate of tree-planting that the Woodland Trust demands is actually quite similar to the peak level seen in the 1980s. So - not too shocking, in reality.

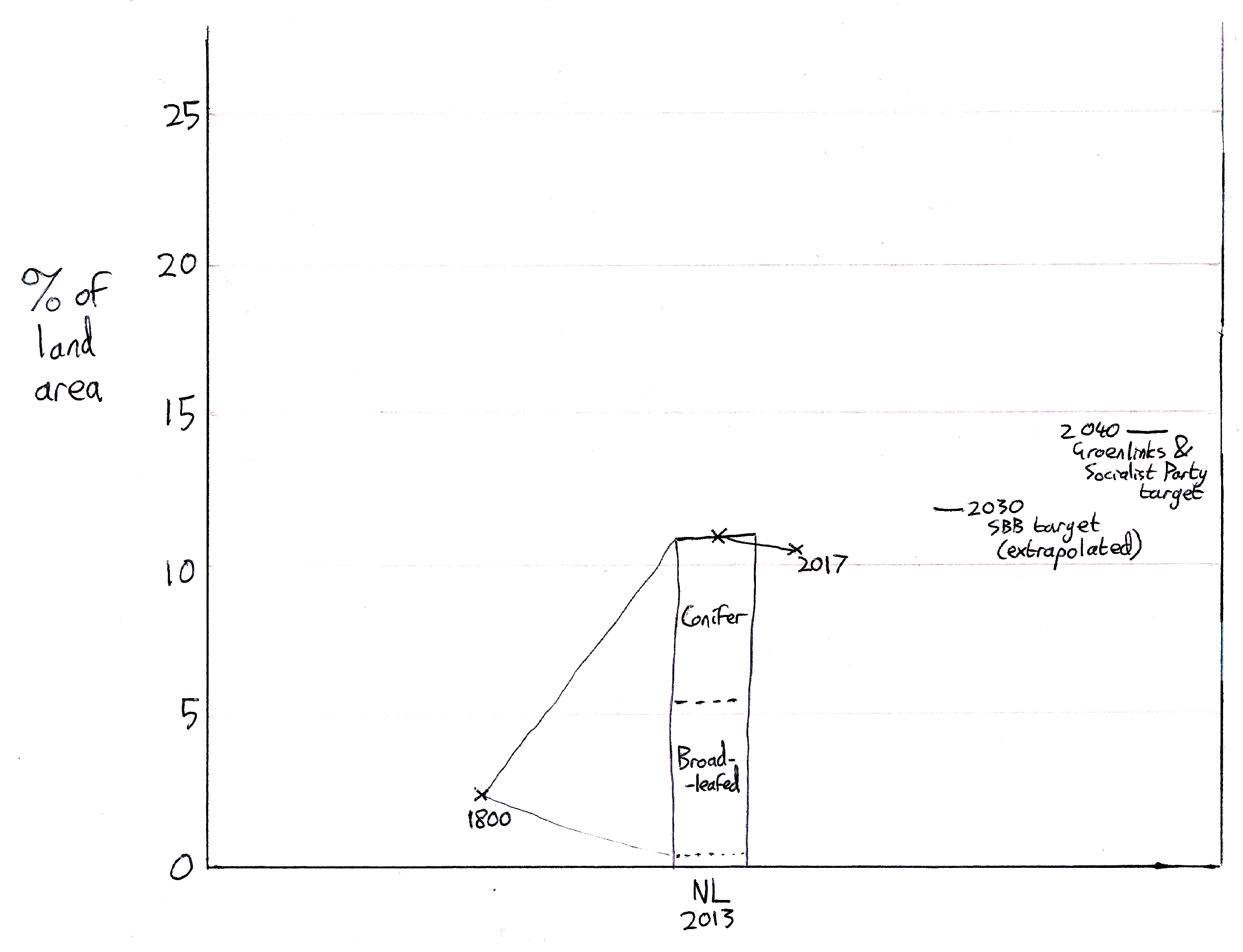

What could we do in the Netherlands? NL doesn't have the forested highlands that Scotland does... it's clearly a different context. Yet surprisingly the amount of forest is quite similar - 11%, versus the UK's 13%. Also just like the UK, about half is traditional broad-leaved forest, and half is conifer.

In fact, from 2013 to 2017 there was a noticeable though small decline in how much of the Netherlands was covered by trees. This sparked a bit of soul-searching among environmental organisations in the country. Natuurmonumenten (a Dutch conservation society) was criticised for its amount of tree-felling, which it was doing for various reasons including biodiversity and to preserve some open habitats such as heath. After this debate it released a statement in April 2019 - for the moment, at least, it would change its policy, and stop cutting down trees except for safety reasons.

Natuurmonumenten is certainly not the only player in the Dutch picture. The European Environment Agency observed in their national reports that "The most extensive flow in the frame of the Dutch natural landscape is the formation of new natural areas, especially of natural grasslands and inland marshes through withdrawal of farming without woodland creation" - whereas for the UK - "Forest creation and management is by far the most intensive flow in the United Kingdom landscape." It's a big difference at the national scale.

And yet, the "Atlas" mentioned near the start of this article shows plenty of Dutch land that could be woodland. Should it be?

One complexity is the various questions around biodiversity, as reflected in Natuurmonumenten's quandary. Some open habitats are important habitats for wildlife such as insects. But there's a big difference between mixed woodland (especially "ancient" woodland) on the one hand, and conifer plantations on the other. The latter are typically monocultures and bad news for biodiversity. An important ongoing process should be to push the balance away from evergreen plantations to rewilded mixed woodland.

There's a noticeable contrast between Friends of the Earth UK, which wants to double tree cover, and Friends of the Earth NL, which has no particular aims for Dutch trees. Instead, they focus on issues of tropical forests (important, to be sure) and other priorities such as reforming agriculture.

It's also understandable that there are more pressing Dutch land-use conversations, such as water management (e.g. giving farmland back to the sea). As part of that conversation, it's worth mentioning that trees can help with issues such as runoff and local flooding: "mature trees can remove 100 litres per day, whereas saplings take [...] approximately 6.5 litres per day" (source).

So yes, there are some ambitions for afforestation in the Netherlands. GroenLinks (the green party) and the Socialist Party together proposed to plant 17 million trees by 2040 - an increase of 2.9 hundredths of the landcover. Staatsbosbeheer (SBB) is the Dutch forestry organisation, and they have concrete plans: they're planning to create 5000 hectares of new forest in the Netherlands over ten years, and also have a partnership with Shell to help restore 1740 hectares of forests that are dying because of ash dieback disease.

Since SBB owns about one-third of the forest in the whole country, they're a big player. Others are the regional provinces - the most ambitious is Noord-Brabant, aiming to plant 13000 hectares. It's not straightforward to add up all these plans to a national picture, but if we assume that SBB's plans are representative, we can extrapolate to get an idea of the ambition compared against the others:

Comparing this view against the UK one, we haven't found any Dutch discussions going quite as far as the UK discussions. Perhaps that's fine. But perhaps it could be a bigger part of the Dutch picture. By the way, another difference we should note: the SBB is an organisation that can directly do these things, not just call for them. So we can take those numbers pretty seriously.

What about the UK - lots of proposals, but... can we implement them? One thorny issue is land ownership - as Simon Lewis points out, in England 1% of the people own 50% of the land. About 13% of the UK is allocated to grouse-shooting and deer-stalking. In the UK, about 70% of forest is in private ownership (versus 50% in NL). These are mind-boggling numbers that could put a spoke in the wheels of any UK reforestation. As Lewis says, it "will require challenging sometimes powerful landowners to act in the interests of wider society". Can it be done in league with these landowners? Or does it need some dramatic changes? A delicate question.

Lewis recommends creating a legal "community right to buy" in England and Wales. It might sound politically ambitious to do this, but such a thing already exists in Scotland, so there's already a clear model we can learn from.

Some closing thoughts:

- The most important priorities (as emphasised by many organisations) are to preserve the existing ancient woodland habitats, and other mixed woodland - and then to increase forest cover through rewilding and mixed native-species woodland, rather than through conifer plantations.

- The Dutch conversation about landuse, in one of the most densely-managed countries in Europe, will continue. The conversation should reflect on the ambitious proposals in the UK and whether they'd be appropriate models.

- The UK should consider the "community right-to-buy" as part of schemes to encourage large-scale rewilding, forest protection, and afforestation.

Read more

- "Rewild 25% of the UK for less climate change, more wildlife and a life lived closer to nature", by Prof Simon Lewis. - and more detail in his "Green New Deal for Nature" report

- "Bos en Hout Cijfers" - stats about forests and trees in the Netherlands (in Dutch)

- "Rewilding will make Britain a rainforest nation again " by George Monbiot